Jakarta. At the height of President Suharto’s tenure in leading Indonesia, the country was famously dubbed an “Asian Tiger” as a testament towards the country’s economic and political strength which reverberated across the international community. However, the country’s culture of cronyism, its questionable human rights record and the unaccountable authority exercised by an exclusive executive branch that carried free reign ultimately led to dire economic consequences. This jolted Indonesia to transform—albeit at a gradual pace.

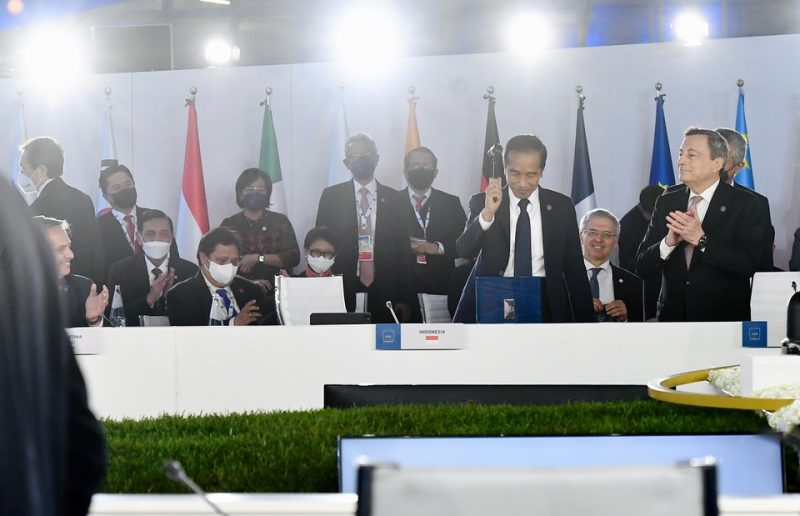

Shifting towards the present day, reform has boded well for the country, with the economy and infrastructure being on President Joko Widodo’s main agenda. Indonesia also now wears many hats, first as an economic and political powerhouse in Southeast Asia determined to roar once again, second as the country coordinator of the US-Asean Special Summit which recently concluded, and third, as President of G20 which marks the first time Indonesia has carried the baton since the G20’s first meeting in 2008.

With Indonesia being laser focused on its pursuit of economic growth and the political influence the country carries, the fundamental question remains whether the G20 can serve as a platform that can support economic growth whilst jointly prioritizing the adherence of business and human rights.

The prevalence of Covid-19 has fostered innovation to accelerate in monumental ways, whether it may be in the goal of curtailing cases or in the shifting of conventional businesses to adapt in a new normal. Indeed, disruption has revealed not only the resilience of a people in a time of crisis but also serves as a reminder of the inequalities found within society.

During a crisis, especially one that has the potency to cost lives, the gap between the haves and the have nots are evident as questions swirl regarding the protection of people without job security, the rising costs from a stalled global supply chain and the enforcements of regulations that put profit ahead of people.

Although the international community has taken great strides in calling to action for nearly a decade through the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP), and even though the framework which upholds protection, respect and access to remedy has been translated into National Action Plans by more than 25 countries including G20 members such as the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan, its impact in improving the climate of business and human rights beyond from expanding corporate social responsibility programs remain to be seen.

At the same time, the G20, which comprises two-thirds of the world’s population and up to 80% of international trade has an influential stake regarding the direction of business and human rights in a regional and global purview. Although the sounding board of human rights has been noticeably absent from the priorities of Indonesia’s G20 presidency, the priority issues presented such as global health architecture, digital transformation and sustainable energy transition requires the adherence of human rights to ensure that innovation navigated through a rules-based order is maintained. Thus, the G20 is an opportunity for countries to chart the next course that can bring business and human rights from principles to practice.

The opportunity for the G20 to take the driver’s seat in steering towards more sustainable practices in business and human rights is supported with precedent. In 2015, the G7—which was then led by Germany—asserted support towards the UNGP and welcomed efforts to develop substantive National Action Plans which would assist in ensuring responsible and accountable supply chains. The G7 at that time also called for greater due diligence for companies and the strengthening of stakeholder initiatives that can promote greater corporate respect for human rights. These priorities come full circle as Germany has taken the helm of the G7 once again this year where they continue to highlight the need for accelerated efforts towards the realization of the UNGP by seizing legislative momentum, collective measures, and the implementation of capacity building.

Hence, the G20 is positioned strategically to communicate ideas vested upon business and human rights. On the Indonesian front, it also serves in the country’s national interest as an accelerated show of reform and a forward-thinking commitment to bring businesses into the accountability of human rights.

The first step in pushing for a human rights based-economy is through the recognition of the importance ingrained within the concepts of business and human rights. This is a crucial focal point for the G20 which can utilize their platform to mainstream the principles of business and human rights as an underlying business model that can be used to achieve their global goals. Furthermore, it should also become a maxim of the G20 to support data-driven research which points that responsible business also equates to a long-term investment that ensures sustainable business practices.

Second, the G20 needs to leverage this influence and authority by leading through example and become a role model for responsible business in the current international landscape.

For example, as G20 president, Indonesia can lead the charge in presenting the building blocks of business and human rights for the digital era as the country is home to approximately 2300 start-ups which comprises decacorns as well as unicorns.

Third, the G20 needs to also present the implementation of business and human rights as a response in developing trends of the future where an aspect of business competitiveness will be measured through corporate responsibility on human rights. In addition, the G20 should further recognize that adherence to business and human rights will become the gateway of investor confidence and consumer preference.

Innovation should not become the ultimate currency that can delay or be served as a bargaining tool when it comes to propping up an economy based on human rights. The spectacular advancements seen in the disruption of industries and the welcoming of digitalization, sustainability and the reform of global health systems are indeed aspects that need to be lauded but we should also make sure that growth benefits the many and not the few.

—

Patricia Rinwigati is Director of the Djokosoetono Research Center, Faculty of Law, Universitas Indonesia. Raafi Seiff is Director of Policy+. The opinions expressed are their own.